- Updated on 28 June 2024

This Article Contains:

What is Internalised Homophobia?

Heteronormativity

Heteronormativity plays a big role in cultivating an environment that encourages internalised homophobia (van der Toorn, Pliskin & Morgenroth, 2020). Some heteronormative beliefs include the idea that people can only experience attraction to the opposite gender. Others involve the the assumption that a person’s gender is aligned with the sex they were assigned at birth idea.

Mediums such as the media, cultural influences, and even social policies may perpetuate the idea that heterosexuality is the expected norm. As a result, heteronormativity influences how LGBTQ individuals view themselves and their preferences.

With heteronormativity regarded as the standard, internalised homophobia is a common phenomenon in the developmental process of LGBTQ individuals (Davies, 1996). Growing up, LGBTQ individuals have to navigate negative societal perceptions surrounding their sexual orientation.

In a qualitative research piece, gay men interviewed shared about their struggles with identity (Cody & Welch, 1997) that often centres on having to distinguish between their self-identity and the negative stereotypes about gay people. In many cases, this struggle is a precursor to the development of LGBTQ people’s self-identity.

Often, internalised homophobia is not something individuals can completely overcome (Frost & Meyer, 2009). It can continue to have a detrimental impact on LGBTQ individuals even after they come out. This can affect their mental health, self-esteem, and general well-being.

How Can Internalised Homophobia Affect a Person’s Health?

Mental Health

Higher Risk of Self-harm

Less Access to Safe Sex Information and Resources

Internalised homophobia also impacts a person’s physical health in many different ways. This pertains especially to sexual behaviour. When a LGBTQ individual has internalised homophobia, they are likely to limit their association with the LGBTQ community. As a result, they have less access to safe sex information and resources. This can expose them to the risk of sexually transmitted disorders.

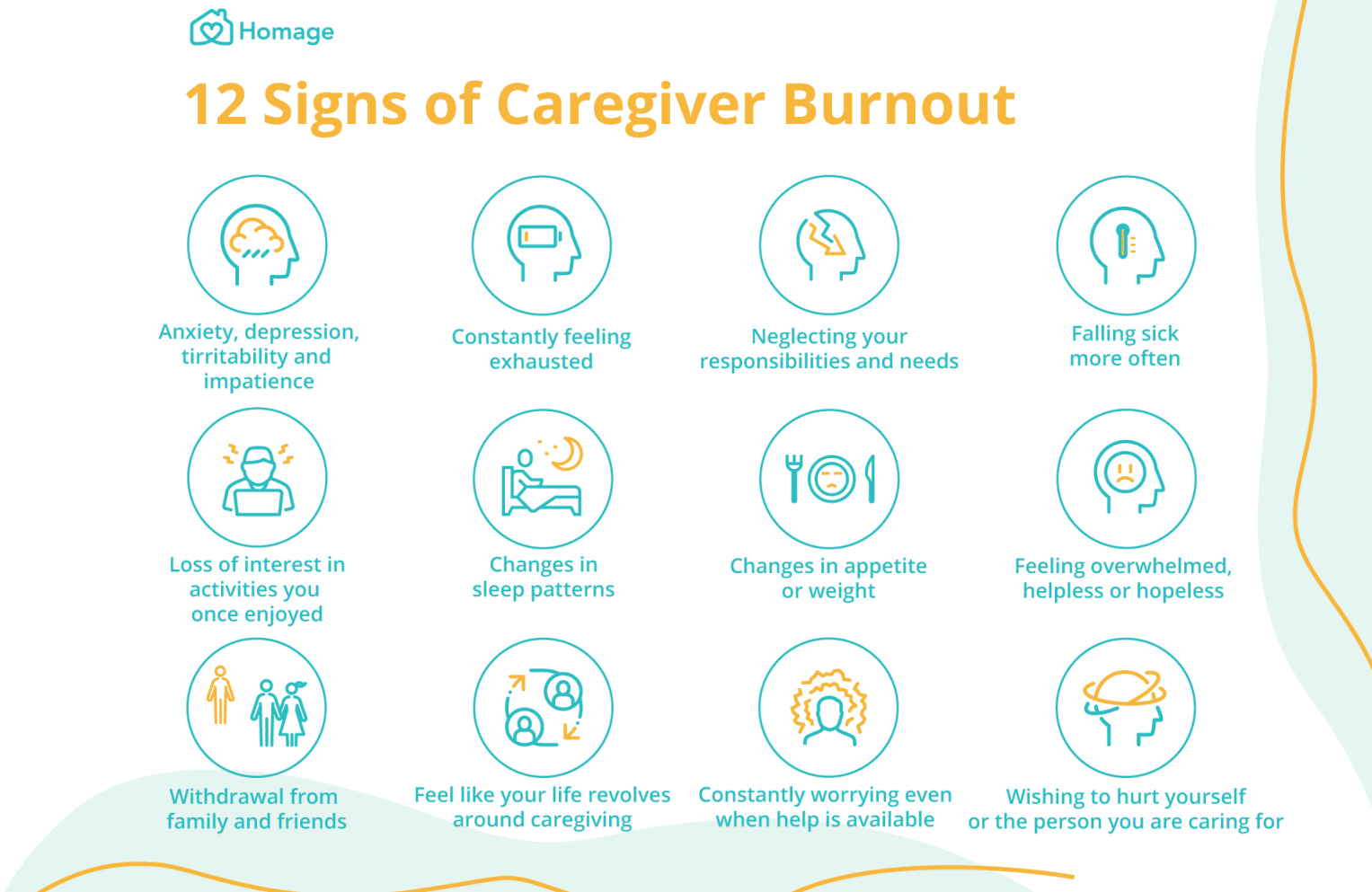

Internalised homophobia can have a devastating impact on a LGBTQ individual’s health in many different ways.

Internalised Homophobia and Depression Levels in LGBTQ Individuals

One's Living Environment

Internalised Homophobia and Relationship Quality among Lesbians, Gay Men, and Bisexuals

Another explanation is that internalised homophobia impedes LGBTQ individuals from coming out. Same-sex couples experience difficulties attending shared social activities where they feel the need to conceal their sexual identity. This can deprive same-sex couples of quality time at family gatherings and work functions. When this concealment is prolonged, there is an emotional cost for both partners (Hatzenbueler, 2009) as their relationship quality is undermined.

If you are in a same-sex relationship, it can be helpful to examine your relationship with your sexual identity. If you find yourself struggling with internalised homophobia, it may be wise to seek professional assistance. Besides supporting your well-being, this would be helpful for your relationship as well. There are therapists who specialise in couple-counselling for LGBTQ individuals. They will be provide you with more knowledge and resources that are specific to your relationship.

Shame and Internalised Homophobia in Gay Men

Support Them as They Form Social Circles

- Surrounding themselves with other LGBTQ individuals can help them establish healthier self-perception. This prompts them to form more positive self-identities.

- Moreover, this allows them to attain the right knowledge and resources that can be beneficial for them. This includes specific information such as preventive measures they can take to ensure safe sex with other LGBTQ people.

Encourage Them to Go for Therapy if They Need It

- LGBTQ individuals are constantly exposed to social pressures surrounding their minority status. Therapy provides them with a safe environment to share their thoughts and process their emotions. It also gives them an opportunity to develop more self-confidence and self-compassion. Furthermore, the therapist can assist them in identifying and addressing any potential mental health conditions or symptoms.

If you find yourself struggling with internalised homophobia, you may find therapy to be a beneficial outlet for you as well. While it may not be severely impacting your everyday life, it can be helpful to speak with a professional and expand on your repertoire of coping skills. The experience of being part of a minority group can be a difficult experience, but sources of support are within reach.

Takeaway

Internalised homophobia is the internalisation of societal prejudice against LGBTQ individuals.

People who struggle with internalised homophobia may feel intense shame and hate themselves and their sexual orientation. This self-hate arises from societal norms that promote heteronormativity as the ‘normal’.

Due to this, queer people may struggle to associate positive feelings towards their identity. Internalised homophobia could lead to potentially harmful conditions such as depression, suicidal thoughts, anxiety, and even self-harm.

Overcoming internalised homophobia often involves seeking support and creating affirming and queer-inclusive social circles.

References

Allport, G. (1954) The Nature of Prejudice. Addison-Wesley, Reading, MA.

Brown, J. & Trevethan, R. (2010). Shame, internalized homophobia, identity formation, attachment style, and the connection to relationship status in Gay Men. American Journal of Men’s Health, 4(3), 267–276. Retrieved from https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1557988309342002

Cody, P. & Welch, R. (1997). Rural gay men in northern New England. Journal of Homosexuality, 33, 51–67. Retrieved from https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Rural-gay-men-in-northern-New-England%3A-life-and-Cody-Welch/48b8160bdcc231c931fce6d19747f97215a4d9bb

Davies, D. (1996) Homophobia and heterosexism. In Davies, D. and Neal, C. (eds), Pink Therapy. Open University Press, Buckingham, pp. 41–65.

Frost, D. M. & Meyer, I. H. (2009). Internalized Homophobia and Relationship Quality among Lesbians, Gay Men, and Bisexuals, Journal of Counselling Psychology, 56 (1), 97-109. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2678796/

Hatzenbuehler, M. L. (2009). How does sexual minority stigma “get under the skin”? A psychological mediation framework. Psychological bulletin, 135(5), 707-730. doi: 10.1037/a0016441

Igartua, K., Gill, K., & Montoro, R. (2003). Internalized homophobia: A factor in depression, anxiety, and suicide in the gay and lesbian population. Canadian Journal of Community Mental Health, 22(2), 15–30. https://doi.org/10.7870/cjcmh-2003-0011

Li, Y. & Samp, J. A. (2018). Internalized Homophobia, Language Use, and Relationship Quality in Same-sex Romantic Relationships. Communication Reports, 00, 1-14. Retrieved from https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/08934215.2018.1545859?journalCode=rcrs20

McLaren, S. (2014). Gender, Age, and Place of Residence as Moderators of the Internalized Homophobia- Depressive Symptoms Relation Among Australian Gay Men and Lesbians. Journal of Homosexuality, 62(4), 463-480. Retrieved from https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/10.1080/00918369.2014.983376

Meyer, I.H. & Dean L. Internalized homophobia, intimacy, and sexual behavior among gay and bisexual men. In: Herek GM, editor. Stigma and sexual orientation: Understanding prejudice against lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals. (pp. 160–186.) Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1998.

Newcomb, M. E., & Mustanski, B. (2010). Internalized homophobia and internalizing mental health problems: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(8), 1019–1029. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2010.07.003

Snively, C. A., Kreuger, L., Stretch, J. J., Watt, J. W., & Chadha, J. (2004). Understanding homophobia: Preparing for practice realities in urban and rural settings. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services, 17, 59-81. Retrieved from https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1300/J041v17n01_05

Spencer, S. M., & Patrick, J. H. (2009). Social support and personal mastery as protective resources during emerging adulthood. Journal of Adult Development, 16, 191–198. Retrieved from https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs10804-009-9064-0

Szymanski, D. M., Chung, Y. B., & Balsam, K. F. (2001). Psychosocial correlates of internalized homophobia in lesbians. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development, 34(1), 27–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481756.2001.12069020

van der Toorn, J. Pliskin, R. & Morgenroth, T. (2020). Not quite over the rainbow: the unrelenting and insidious nature of heteronormative ideology. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 34, 160-165. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2352154620300383

Williamson, I. R. (2000). Internalized homophobia and health issues affecting lesbians and gay men. Health Education Research, 15 (1), 97-107. Retrieved from https://academic.oup.com/her/article/15/1/97/775710

Yolaç, E. & Meriç, M. (2020). Internalized homophobia and depression levels in LGBT individuals. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care, 57, 304-310. Retrieved from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1111/ppc.12564